Why We Created an Anti-Prize: On Poetry Awards, Indie Presses, and the Myth of Prestige

Poetry prizes are everywhere. So are prize-nominated books, prize-listed poets, and presses (not so) quietly using awards as a marketing strategy. Ugh!

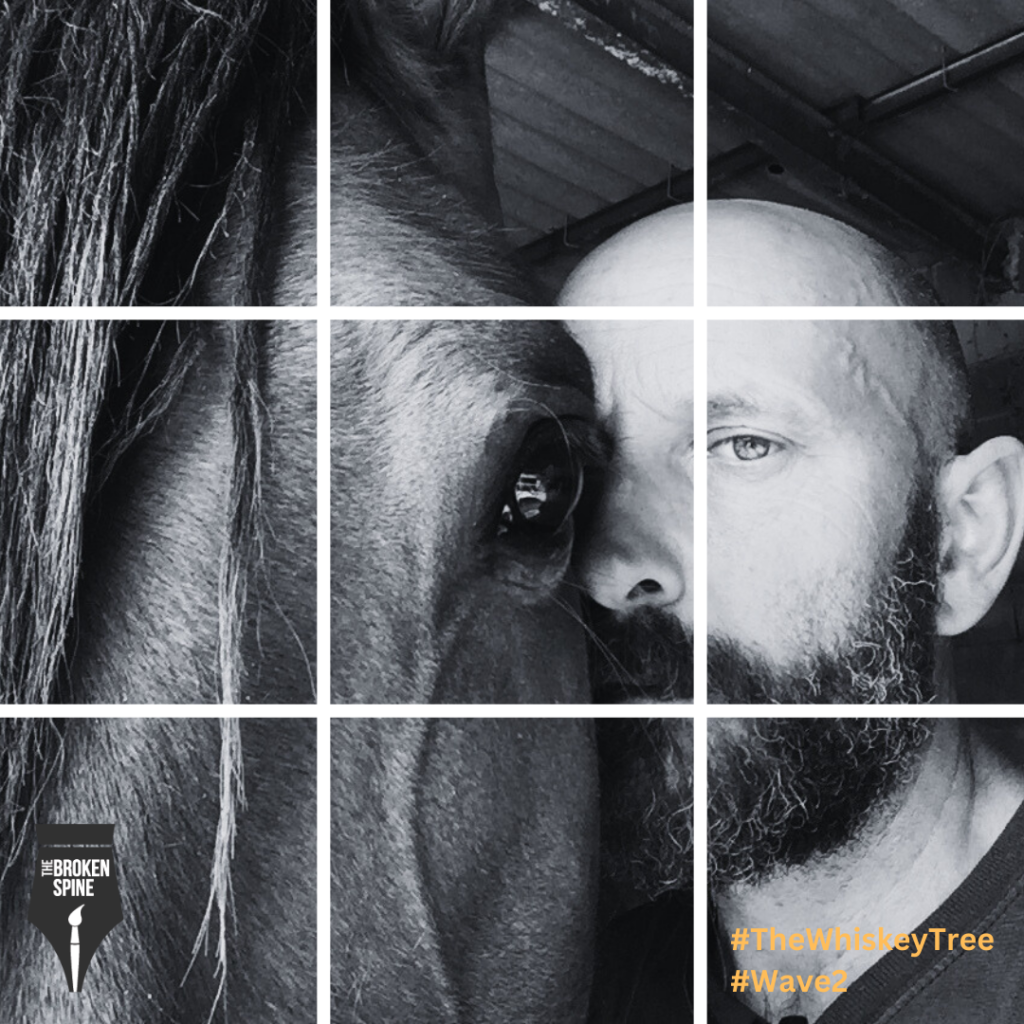

James McConachie is the kind of poet who doesn’t chase the page, he lets the poem walk in, muddy boots and all, and take up space. His work isn’t fussed with artifice or trend; it lives in the world, in solitude, in human absurdity and quiet heartbreak. He writes like someone who’s lived a full chapter or three before returning to the pen with a sharper eye and less patience for bullshit. “Well, my first poetry was doubtless some wretched juvenilia,” he says, half-amused, half-horrified. “I can still remember some lines I wrote that make my toes curl 40 years on.” But he’s under no illusions. “Hopefully things have improved since then.”

They have, markedly. McConachie credits age and experience with softening his observational lens. “I think age and experience have made me a kinder, rounder observer of people,” he says. These days, it’s often simple people-watching that inspires the poems he’s fondest of. His perspective is uncluttered, not because he lacks depth, but because he’s trimmed the unnecessary. “It’s a relatively uncluttered perspective that comes with having been round the block a bit.”

The moment that pulled poetry back into his life wasn’t academic, it was fevered, feral. “A raging fever I developed on a dangerous horseback trip,” he recalls. In its aftermath, he wrote about the experience in prose, but it was the language of poetry that reignited something deeper. “Leaning into my fever dreams, I rediscovered a love of the freedom with language only poetry can really afford us.” The way he says it, “Possibly”, suggests he’ll never give poetry too much credit. But it’s clear it grabbed him and didn’t let go.

When a poem starts to form, McConachie drops everything. “I put everything else to one side, if possible, and prioritise the poem.” It’s not indulgence, it’s necessity. “It’s worked well for me, establishing it as a serious endeavour of worth, more important than cleaning the bathroom or hanging laundry.” The poems come quickly, mostly intact. “I don’t fettle away at my poems very much,” he says. “They emerge quite quickly and I tweak a little bit here and there, usually for the musicality, the pleasure principle, if you will.” And when it’s done? He cuts it loose. “I’m a definite believer in the idea that a poem is never finished but just abandoned.” There’s a slight irreverence in how he treats the craft, but that irreverence is earned, and shot through with honesty. “Perhaps this is a bit cavalier… but I’m old, and impatient.”

Structure isn’t planned, it simply shows up. “Structure seems to emerge by accident,” he says. “‘Oh, this is in stanzas of 3 lines then? Ok.’” There’s no pretence about poetic technique here, just an openness to where the language wants to go. “I’m quite a boisterous defender of my wilful know-nothing approach as a liberating ignorance.” If he’d studied it formally, he suspects, he’d have worked “the life out of it, like scone dough that’s had too much handling.”

Living in Spain, far from the culture he was born into, has fed McConachie’s work in unpredictable ways. “I suppose being immersed in a culture not my own has given me lots of stuff to gawp at.” Spain is a visual place, its landscapes, its architecture, its contradictions. “I walk, almost always alone, through the mountains and forests… the rhythm of walking or maybe the blood-oxygen seems to stimulate me.” Even something as mundane as a bus ride becomes a trigger. “Catching the bus to anywhere, usually Barcelona, is an incredible opportunity for people watching in Spain—the old nun who always gets on at the same stop, the nervous Senegalese boy texting his mum… there’s always so much to take in.”

McConachie lives in an isolated farmhouse, no neighbours, just animals, landscape, and time. He often spends days without speaking, leaving only when it’s absolutely necessary, maybe for bread. “There is a long-wavelength calm in the landscape here, concentrated by solitude,” he says. “I’m not sure I could ever live anywhere in sight of another house ever again.” His writing desk, handmade, by a balcony, faces the fields. He jumps up to watch birds mid-sentence. “I just did, for example, to see the first bee-eaters below the house.”

But poetry didn’t just return through beauty and isolation. There was pain, prolonged heartbreak, long shadowed depression. “It was really a prolonged and corrosive heartbreak and an equally prolonged period of depression that jolted me into writing poetry,” he says. Often, the poem begins with something festering inside him. “Then, like any divination tool—astrology, I Ching—it seems to hold up a mirror to the subconscious.” It’s not therapy. It’s revelation. Writing and reading poetry, he says, has brought him closer to a kind of essentialism. “A worldview of the human condition as unnecessarily miserable and complicated.”

McConachie’s debut collection, Consolamentum, was published by Black Bough in 2024. The title nods to catharsis, to spiritual simplicity, and the painful process of refining both life and language. It’s a book written with one foot in the old world and one hand reaching through the fog of memory, silence, and solitude.

This is poetry without pretence. It’s built from blood, walking rhythm, and the pleasure principle. The kind of work that doesn’t explain itself, but stays with you, like the sound of your own breath on a mountain trail.

Poetry prizes are everywhere. So are prize-nominated books, prize-listed poets, and presses (not so) quietly using awards as a marketing strategy. Ugh!

On Saturday 31 January 2026, The Broken Spine Live rolls back into Southport for an evening of raw words and real ale,

Gig Review: Stereophonics at M&S Bank Arena, Liverpool – 16 December 2025 I have loved Stereophonics since the day I bought Local

The Broken Spine is a poetry and arts collective proudly published on the coastal edge of North-West England. Founded in 2019 by Alan Parry and Paul Robert Mullen – two school friends reunited after twenty years through a mutual love of poetry.