Why We Created an Anti-Prize: On Poetry Awards, Indie Presses, and the Myth of Prestige

Poetry prizes are everywhere. So are prize-nominated books, prize-listed poets, and presses (not so) quietly using awards as a marketing strategy. Ugh!

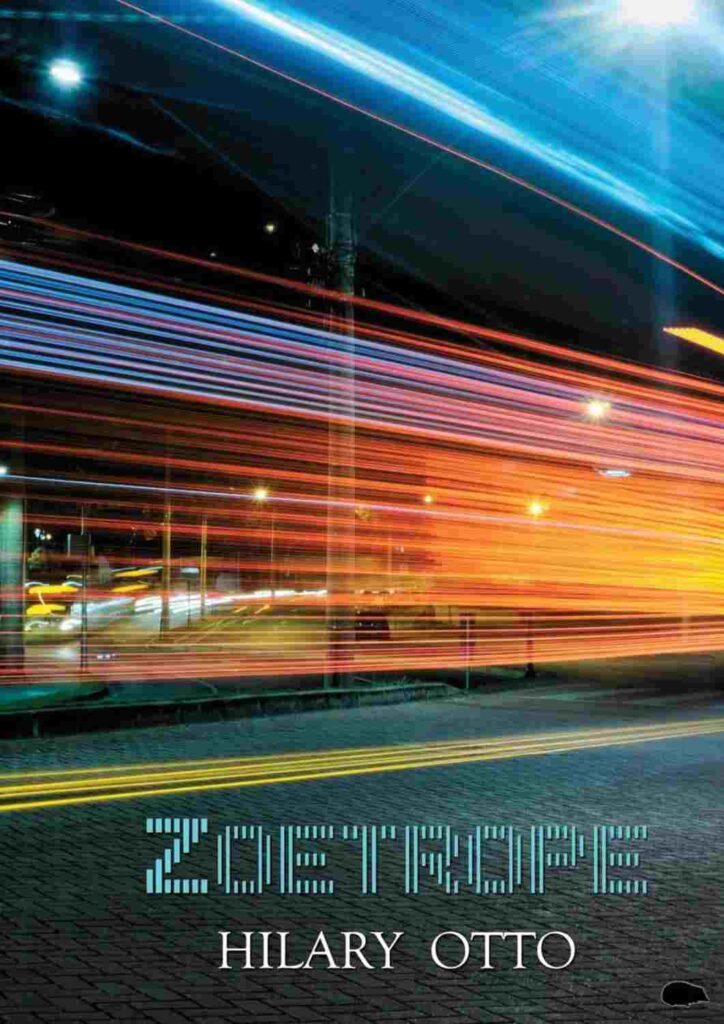

Hilary Otto’s Zoetrope (Hedgehog Press) doesn’t ease you in, it throws you headfirst into its spinning frame, like an antique toy stuck on fast-forward. From the jump, Otto tells us what kind of ride this is. The opening poem references “bold in the morning light” illusions, a line that undercuts itself as soon as it lands. This is not a collection for those seeking lyrical comfort or narrative balm. The Illusion of Motion sets the thematic table: “I look like I am moving forward. / I reach back into the dark.” The couplet lands like a sock to the jaw, exposing not just a personal paralysis but a broader cultural malaise. Otto’s poems move like zoetropes, flickering between past and present, real and projected, unsettling the reader by revealing the machinery beneath perception itself.

The domestic sphere, too often reduced to Instagram polish or feminist shorthand, is where Otto sharpens her teeth. In A Mother’s Work, maternal care becomes its own occult rite: “I spread these visions as offerings / to appease the demons that possess me.” This isn’t sentimental. It is survival under duress. Parenting here isn’t love’s gentle labour; it’s haunted reckoning. Otto renders these spaces with clarity and menace, refusing to look away from their latent horrors. Then there’s Dinghy, a poem that rewires childhood nostalgia into dread. “And when we saw he’d gone we didn’t speak of him.” That silence is louder than anything else in the book. It’s the trauma buried in the syntax. It’s Otto trusting us to hear what isn’t said.

Otto’s formal play isn’t just clever, it’s strategic. In Scarab’s Got Talent, she turns the dung beetle into a kind of cosmic clown, part Icarus, part insect: “I wanted to be the one to watch, to be Betelgeuse.” It’s absurd, yes, but heartbreakingly so. The pantoum form loops and folds in on itself like the creature’s own grim choreography. Otto uses form not as ornament, but as argument. Repetition becomes burden. Ambition becomes spectacle. There’s craft here, sure, but more than that, there’s purpose.

When Otto trains her gaze on the political, the collection goes from smart to scorching. Ties pulls no punches: “it creeps back, tightens its colonial noose, / binds us to its maleness.” The line is blunt by design, anger honed into edge. And in The Nation’s Favourite Poem, she does something quietly devastating, she reprints Kipling’s If, unaltered, and lets its imperial rot speak for itself. It’s a brutal gesture. No satire, no remix. Just context. And that’s enough. Otto forces us to reckon with what still gets canonised and why. It’s a critique of literary gatekeeping dressed as an editorial decision. That’s how you weaponise curation.

Zoetrope is more than a poetry collection. It’s a trapdoor beneath the spinning stage of modern life. Otto’s work reminds me of what first drew me to the independent publishing scene, the refusal to conform, the insistence on speaking plainly about chaos. This is poetry that doesn’t care if it’s palatable. Thank fuck for work like this! It wants to say something true. And in doing so, it earns its place alongside contemporary heavyweights. Zoetrope doesn’t ask you to keep up; it dares you to stop and look. Like, really look. Before the next frame flickers past.

About the Author

Hilary Otto is an English poet based in Barcelona. Her poems have appeared in Ink, Sweat and Tears, The Alchemy Spoon and Popshot among other journals; and in anthologies from Live Canon, Nine Pens, Sídhe Press and Fevers of the Mind. She won the Hastings Book Festival Poetry Competition 2022.

Poetry prizes are everywhere. So are prize-nominated books, prize-listed poets, and presses (not so) quietly using awards as a marketing strategy. Ugh!

On Saturday 31 January 2026, The Broken Spine Live rolls back into Southport for an evening of raw words and real ale,

Gig Review: Stereophonics at M&S Bank Arena, Liverpool – 16 December 2025 I have loved Stereophonics since the day I bought Local

The Broken Spine is a poetry and arts collective proudly published on the coastal edge of North-West England. Founded in 2019 by Alan Parry and Paul Robert Mullen – two school friends reunited after twenty years through a mutual love of poetry.