James B Partridge Brings ‘The Big Christmas Assembly’ to Liverpool — and It’s a Festive Throwback You Won’t Want to Miss

M&S Bank Arena Auditorium | 23 November 2025 If you ever belted out “Shine Jesus Shine” with more passion than a West

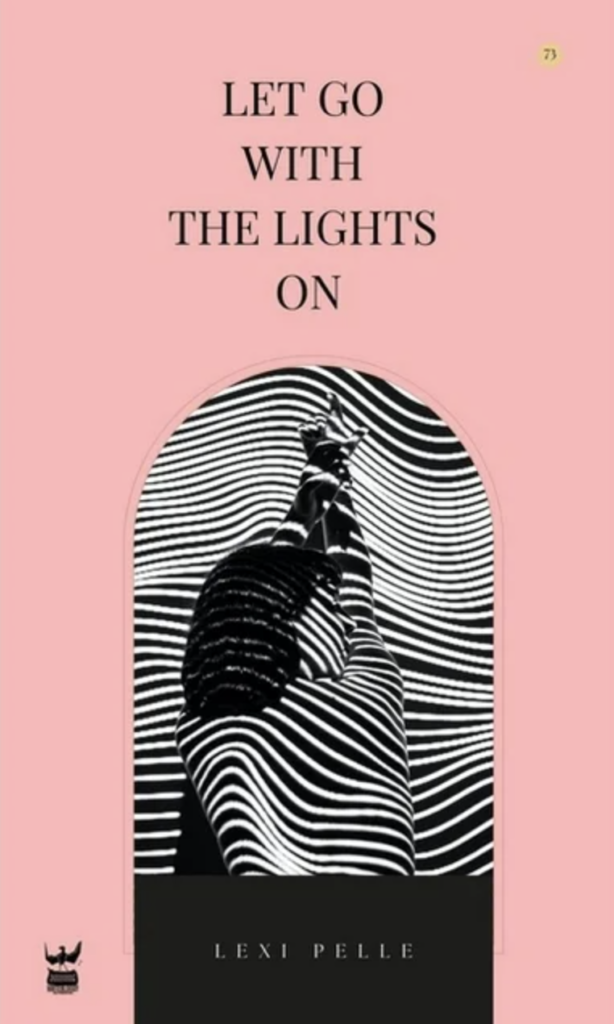

Lexi Pelle’s Let Go With The Lights On (Write Bloody Publishing) is a debut collection that doesn’t blink. It looks long and hard at everything: the plastic gloss of girlhood, the awkward shapeshifting of adolescence, the lure and violence of desire, and the tangled underwire of faith and shame. This isn’t a tidy confessional. It’s an electric scrapbook of elegies and odes, satire and sincerity, shaped with cinematic precision and radiant fury. Think early Sofia Coppola with teeth. Pelle builds a world where everything, Diet Coke, a strapless top, a pair of tweezers, brims with tension and metaphor, but the book never slips into abstraction. It stays bodily. It stays human. It knows its stakes. And boy, does it deliver!

The collection opens in memory’s wardrobe: a blue skort, a purple bandeau, a pink cheetah print coat. Each piece of clothing is more than fabric, it’s costume, rebellion, camouflage. I have written on fashion and masculinity myself, I found this take especially interesting as a consequence. In The Skort, Pelle writes, “what is your collective noun? / A communion. Hesitation. / A misdemeanor?”—a moment that captures the poet’s central concern: how girlhood is both public and policed, sacred and suspect. These early poems interrogate beauty rituals with biting humour and vulnerability. In 2000’s Eyebrows, she recalls tweezing “tiny tire irons onto our faces” and concludes, “I’ve spent years trying to grow out / the look of surprise on my face.” It’s funny, yes, but also incredibly sad. As such, the laugh sticks in your throat.

Pelle’s observational eye is relentless, but never cruel. Her portraits of the mother figure are among the most layered in recent poetry. In Diet Coke, she renders her mother’s habit with sharp affection: “I thought it tasted like a backhanded / compliment… / a supermodel’s saliva.” The poem is a masterclass in poetic analogy, startling yet precise, tinged with resentment and reverence. Ode To My Mother’s Thong revisits this dynamic with even more clarity, watching her mother reach for bargain bread while her underwear peeks out: “I’d see it… and remember being mad that she’d do this, / be beyond me, not my mom.” Pelle isn’t moralising; she’s holding up the glitter and grit of femininity, asking what it costs and who pays.

But what makes this collection truly stand apart is how it elevates the mundane into the mythic. In Mary, Pelle reimagines a nativity play as a personal revolt. After stuffing a plastic baby Jesus up her dress, she screams “like I’d heard / the women giving birth on TV do.” It’s hilarious, yes, but also devastating: the girl learning that to embody the sacred is to be punished for it. The poem ends with a heat that “seared us both,” an indictment of both institutional shame and the girl’s hunger for realness.

Religion threads through the collection as both haunt and hook. Prayer, a poem inspired by Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still #25, declares: “Like God, Girlhood is a kind of middle distance.” That line alone could be the thesis of the book. Pelle’s faith is complicated, lapsed, but never indifferent. In Did You Know The Vatican Is Made Of Particle Board, she recounts a moment of gullibility, then reframes it: “Who doesn’t want the world to be / made of softer material?” This is what Pelle does again and again, cracks the hard icon open to reveal something tender inside.

Desire is another key engine here, explored in both tender and troubling registers. In Bleach and Tone, a man kisses the speaker by mistake, and she barely reacts: “She looks into her lap. No one says / anything over the blow dryers.” It’s a poem about the ways women are trained to metabolise intrusion. But later, in The Bats Are Having Non-Penetrative Sex In A Church, Pelle finds absurdity and grace in the details of animal intimacy. “Like Christian kids, / hopped up on guilt / and hormones, looking / for a loophole.” This blend of sass and science, irreverence and awe, is signature Pelle.

Formally, the collection thrives on rhythm and enjambment. The lines move like conversation, but they’re sculpted. Pelle is often funniest when she’s most precise. In Goods, a moral crisis at CVS becomes an existential pivot: “Morality, that meat-eating / plant, bloomed muscular guilt / in my gut.” These metaphors don’t do more than decorate, they drive the narrative forward. Likewise, in She Of Theseus, the speaker proclaims, “I don’t hate myself, I / hate the idea that I might / miss out on all the selves / I would have fun being.” That line lands like a revelation. It crystallises the book’s deeper philosophy: identity is not fixed. It’s a dressing room of selves we might, or might not, live into.

If there’s a flaw in this book, it’s that some poems veer a little too close to their sources (pop culture, Instagram theology, Rupi-adjacent sentiment) but Pelle always pulls it back with a killer line or unexpected swerve. Let Go With The Lights On is not content to bask in the glow of aesthetic melancholy. It wants more. It reaches. It risks.

This is a work that knows the sacred is in the detail, that prayer can be found in a thong, and that even when nothing fits, the trying-on matters. Lexi Pelle has written a vital debut, glittering with sincerity and spiked with resistance. It doesn’t ask to be loved. It dares to be seen.

About the Author

Lexi Pelle is a poet and editor living in New Jersey. She was the winner of the 2022 Jack McCarthy Book Prize, a Pushcart Prize nominee, and a finalist for the Prufer Poetry Prize, Crosswinds Poetry Prize and the Marvin Bell Poetry Prize. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Rattle, Ninth Letter, Plume, SWWIM and The Shore.

M&S Bank Arena Auditorium | 23 November 2025 If you ever belted out “Shine Jesus Shine” with more passion than a West

Carrie-Anne Ingrouille directs a bold new revival of the cult classic musical at the Playhouse, 3 Dec 2026 – 9 Jan 2027

Children’s literature often gets pushed to the side in the “serious” literary world—dismissed as cute, simple, or somehow less worthy of analysis

The Broken Spine is a poetry and arts collective proudly published on the coastal edge of North-West England. Founded in 2019 by Alan Parry and Paul Robert Mullen – two school friends reunited after twenty years through a mutual love of poetry.